In this essay, I address Part I, Chapter I, The Adventure of the Hero: Departure, of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.[1] In particular, I focus my analysis on four key elements of the Departure stage; these being The Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, The Crossing of the First Threshold, and (in brief) Supernatural Aid. I compare and contrast Campbell’s monomyth narratology with the early chapters of Clive Staples Lewis’ children’s classic, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, identifying the application of the selected elements of the Hero’s Journey in Lewis’ story.[2]

Synopsis of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

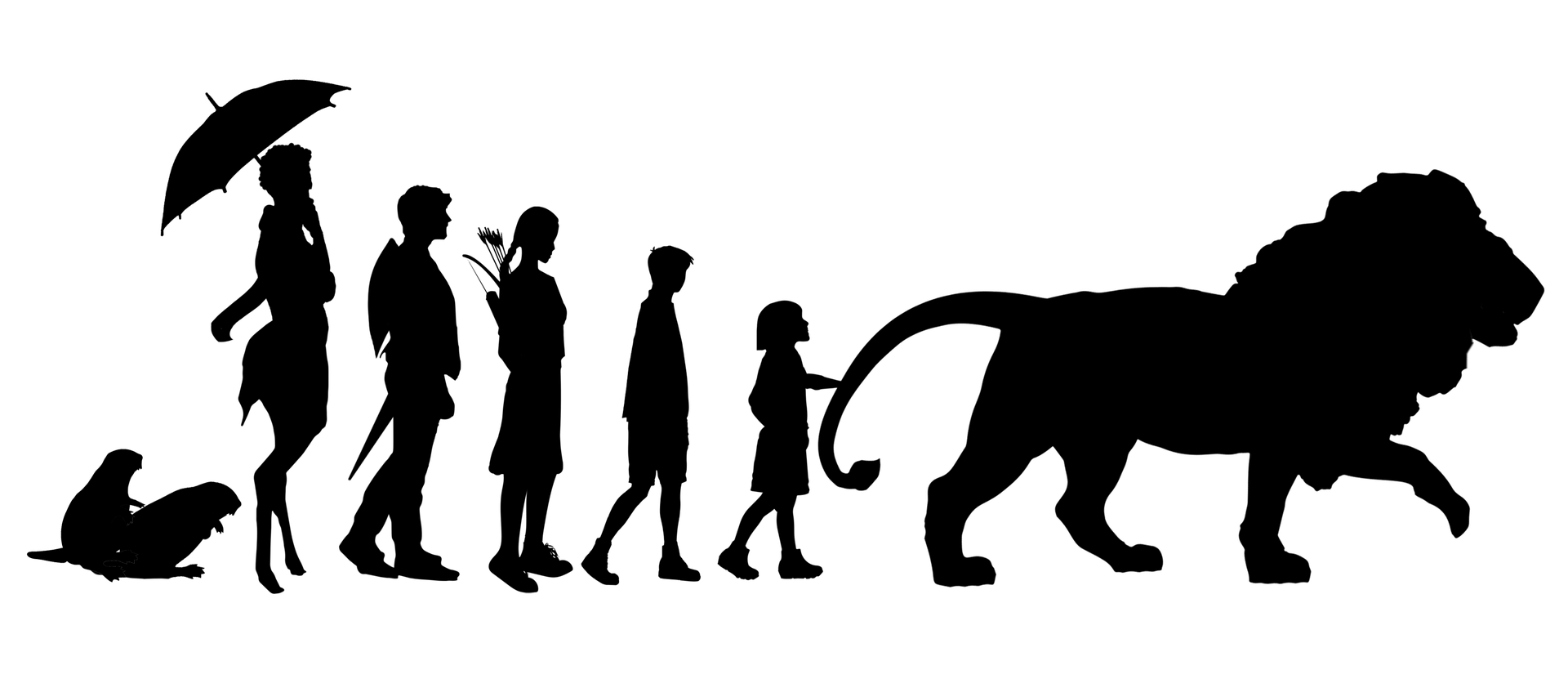

It is 1940s Britain. At the start of the story, four sibling children with the surname Pevensie: Peter (aged 13), Susan (aged 12), Edmund (aged 10), and Lucy (aged 8), are evacuated from London, because of German bombing raids, to the country house of Professor Digory Kirke, who is unrelated to them. While exploring the house, the children discover a room with an enormous wardrobe–a disguised magical portal to the realm of Narnia, ‘where it is always winter but never Christmas,’ ruled over by the White Witch.[3] Lucy discovers Narnia first and, supported by the Professor (who, unknown to the children initially, had been to Narnia as a boy), convinces her doubting siblings of the possibility of its existence. All four pass at last into Narnia together. As part of their adventures, they meet exotic, talking Narnian creatures drawn from fairy tales, legend, and folklore, including Aslan the great creator-lion. High adventure follows, full of treachery, battles, and sacrifice.

The Call to Adventure

The call to adventure occurs early in Lewis’ story. On their arrival at Professor Kirke’s expansive home, the children expect they will be free to explore the local area the next morning for badgers, foxes, rabbits, and other wildlife. A steady downpour of rain instead confronts them, prompting Susan to propose listening to the wireless or to read a book, to which Peter announces his intention to explore the house. Lewis writes, ‘everyone agreed to this, and that was how the adventures began’ (Lewis, p. 14). Peter is, therefore, an instigator of The Call to Adventure; however, I would contend his was not the first call–another hand was at play.

The non-human herald ‘calling’ (or prompting) the children to adventure is the weather. If this had not been so, they would not have explored the house and discovered, in time, the room that was empty, except for the presence of a single, sizeable wardrobe. Not finding anything in the room other than the wardrobe, the three older children leave, disappointed. This, I would argue, is the first evidence in Lewis’ book of a Refusal of the Call, if one were to accept that divine forces were at play, which had been ‘beckoning’ the children to the disguised portal (the wardrobe) and into another, magical world.

However, Lucy’s childlike curiosity tempts her to remain in the room when the others depart, and she tries the door of the wardrobe. Had divine forces not intended that she (or anyone else) should enter the interior of the wardrobe, then it is reasonable to assume Lucy would have found it locked, with the key absent. Indeed, Lewis writes, ‘[…] she felt almost sure that it would be locked. To her surprise, it opened quite easily, and two mothballs dropped out’ (Lewis, p. 15). On entering the interior, the youngest of the troop pushes through rows of fur coats, feeling for the rear of the wardrobe and, not finding it, perseveres regardless, so passing–unplanned and unknown–through the portal and into the land of Narnia. The Crossing of the First Threshold has occurred. As Campbell states, ‘this is an example of one way in which the adventure can begin. A blunder–apparently the merest chance–reveals an unsuspected world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood’ (Campbell, p. 51).

We can see a parallel blundering into an unexpected world in the work of another children’s author, Lewis Carroll, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.[4] Here, a bored Alice sits by a riverbank and watches as the White Rabbit–wearing a waistcoat and carrying a pocket watch–disappears down a rabbit hole. She follows and becomes embroiled in a fantasy world full of anthropomorphic characters. Alice has accepted The Call to Adventure and The Crossing of the First Threshold occurs.

Where the Refusal of the Call becomes impossible with Carroll’s character, Alice, once she has fallen (literally) into a world of trouble from which she must then ingeniously extricate herself, the older Pevensie children in Lewis’ story refuse their call to adventure initially by doing an about-face and walking out of the room. However, at apparent variance with Campbell’s portrayal of this part of the Hero’s Journey, they are granted a second (and subsequent) opportunity to accept the call, following Lucy’s excited statement to her siblings about her magic portal discovery, ‘it’s a magic wardrobe. There’s a wood inside it, and it’s snowing, and there’s a Faun and a Witch and it’s called Narnia; come and see’ (Lewis, p. 32). Lucy’s siblings do not believe her and tease her. They refuse the call yet once more.

Days later, during a game of hide-and-seek, Edmund follows Lucy into the wardrobe and crosses the threshold (again, unaware) into Narnia, so meeting The White Witch, the evil ruler of Narnia. Upon his return to the house with Lucy, Edmund lies to Susan and Peter, because he can be spiteful, and claims there is no such place as Narnia; Lucy had been making the story up. At this moment, there is yet another Refusal of the Call. However, as Campbell states, ‘[…] even though the hero [in this case, Lucy] returns for a while to [her] familiar occupations, they may be found unfruitful. A series of signs of increasing force will become visible […] the summons can no longer be denied’ (Campbell, p. 56). Campbell says further, ‘this first stage of the mythological journey–which we have designated the “call to adventure”–signifies that Destiny has summoned the hero’ (Campbell, p. 58). All four children will at last heed the call.

I would argue that evidence of these signs [Destiny’s call] is both tangible and intangible, the full significance of which the children appear unaware. For example, the wardrobe is without question real. However, it is–to the older children at least–merely an imposing wooden construction that acts as a doorway to the land of Narnia; it is Lucy who always considers it ‘magical’ in nature. What the children do not yet comprehend in full is the wardrobe’s true magical origin, hence its apparent ability to ‘beckon’ them several times to return to it and pass across its literal and magical threshold into another world. Constructed from the wood of a magical fruit tree, it started life as a seed from an apple brought back by Digory Kirke (later, Professor) from Narnia, produced by The Tree of Protection.

With the continuation of The Hero’s Journey, it is not until Chapter Six, however, that all four at last enter Narnia together, with Peter observing, ‘[…] why, I do believe we’ve got into Lucy’s wood after all’ (Lewis, p. 62). Their arrival into Narnia had, once again, resulted from an unexpected incident, with the hand of fate seeming to guide them when the Professor’s housekeeper, Mrs Macready–who was not fond of children–was showing a party of visitors about the house and closing in on the children’s location. The children duck into the room with the wardrobe and climb in when they see the handle of the door to the room being turned, and ‘that was how the adventures began for the third time’ (Lewis, p. 59).

There is merit in expanding the Supernatural Aid aspect of Campbell’s Departure stage. For we can see from what I have so far presented that it appears preordained for the Pevensie children to discover Narnia, despite The Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, and The Crossing of the First Threshold occurring several times. As Como states,

[…] with the help of many brave Narnian creatures […] they defeat the White Witch. Winter ends. The Pevensies become royalty in this recognizably medieval world, with Peter as the High King, for they are the Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve whose arrival has been prophesied for a long time (Como, p. 77).

However, the outcome of the events cited by Como above would have been potentially impossible to achieve had not the Pevensie children received aid from countless others in their adventures, in particular from two notable agents of Supernatural Aid: Professor Kirke within their world, and Aslan the great creator-lion in the land of Narnia. Both characters conform to the Supernatural Aid aspect of Campbell’s Departure structure.

In this essay I have addressed specific elements of the Departure phase of the Hero’s Journey as detailed in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, identifying and discussing those same elements within the opening chapters of C. S. Lewis’ children’s classic, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. In doing so, I endorse Lewis’ work as an exemplary example of this part of Campbell’s traditional monomyth story structure.

Works Cited

[1] Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (London: Fontana Press, 1993).

[2] Clive Staples Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Chronicles of Narnia, 2 (London: Collins, 1998).

[3] James Como, C. S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction, The Oxford Very Short Introduction Series, 1st edn (London: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[4] Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, ed. by Hugh Haughton, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Nos. 1 & 2 (London: Penguin Books, 2003).

[Header image: Cropped front cover image of the full-colour collector's edition of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C. S. Lewis. Cover illustration © Pauline Baynes].

Bibliography

Campbell, Joseph, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (London: Fontana Press, 1993)

Carroll, Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, ed. by Hugh Haughton, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Nos. 1 & 2 (London: Penguin Books, 2003)

Como, James, C. S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction, The Oxford Very Short Introduction Series, 1st edn (London: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Lewis, Clive Staples, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Chronicles of Narnia, 2 (London: Collins, 1998)

Image credits

Header image: Cropped front cover image of the full-colour Collins collector's edition of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C. S. Lewis. Cover illustration © Pauline Baynes.

Narnia character silhouette: image by Jenneth from Pixabay.